20 May 2013

THESE ARE THE VOYAGES: I SENSE NO EMOTION, ONLY PURE LOGIC

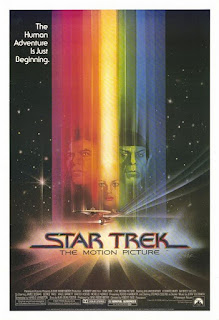

I weep for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, as I would for a brother. Honestly. Rechristened by audiences as The Motionless Picture almost from the instant it opened in December, 1979, it has never once shaken the reputation of being a joyless slog, neither pleasurable in its own right nor remotely successful as a big-screen followup to the 1966-'69 TV series Star Trek, and subject to the worst indulgences of pretentious science fiction of the late '70s. And all these things are true, to a degree, though the film gets beat up too much, treated with a sort of caustic recoil that it does not earn. This is merely a weak, inapt Star Trek movie, not a completely awful one.

Hindsight makes the movie much easier to take, certainly: both in knowing that compared to something as spectacularly worthless as Star Trek: Nemesis, The Motion Picture is pretty decent, in fact, and also in knowing that with genuinely excellent movies in the franchise's immediate future, it doesn't have to bear the weight of being "The Star Trek movie we've been waiting for all these years", but merely a Star Trek movie, one of many. Still, it's easy to understand what a singularly deflating experience it must have been for the first audiences, who'd been keeping the fires lit for the series ever since it was unceremoniously cancelled a decade earlier, only to find its bright, Western-influenced sense of space adventure replaced by a lugubrious sense of self-seriousness in which the free humor of the TV show had been banished to a few character moments included more as a sop to the fans than an integral part of the movie.

This state of affairs was by no means an accident. The reason that a half-decade of attempts to launch a Star Trek feature, or a new TV series (under the name Star Trek: Phase II) finally ended in success has nothing at all to do with the dogged perseverance of creator Gene Roddenberry, and mostly because in 1977, Star Wars made an amount of money that you wouldn't have even joked about before it opened. Overnight, every studio wanted their own massive sci-fi epic to jump on that bandwagon ASAP, and Paramount had the good fortune of already owning a sci-fi franchise with a built-in fanbase and something like brand recognition even among those who weren't fans. It even had "Star" in the title. On the other hand, the people responsible for bringing Star Trek to cinemas were eager to distinguish their property from George Lucas's rousing but trivial space opera, by emphasising the philosophical side, the serious side, the "hard" side of Star Trek. A series that had never, before 1979, ever had the slightest inclination towards hard sci-fi.

So the expectation that The Motion Picture would be something like Star Wars but with more humanism and a sense of exploration rather than action - would be the thing the show always was - was already doomed by the time that a shooting script was finally selected out of God knows how many false starts. But faulty expectations aren't reason enough to declare The Motion Picture an outright failure. In fact, there's a lot about the movie that works: starting with the selection of Robert Wise as director, easily the most talented man ever put in charge of a Star Trek feature, and at the level of pure cinematic language, The Motion Picture is still probably the "best" movie in the franchise; most of them have the unmistakable aura of TV directors hanging around, but Wise was unmistakably looking to make a real, proper feature film - a Motion Picture if you will, and not just a movie like the subsequent eleven Star Trek pictures - and divorced from anything else, he succeeded. The Motion Picture is a gorgeous movie, with the best visual effects of 1979; it had the pedigree for it, with the visual effects team led by Douglas Trumbull, of the groundbreaking 2001: A Space Odyssey and the exemplary Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Star Wars' own John Dykstra.

In fact, the outstanding visual effects work is directly responsible for one of the easiest and most accurate criticisms of the movie: some much time and energy and money was spent perfect the VFX, and in those days, effects of this kind were so excitingly novel, that a deeply unnecessary percentage of the film's running time is devoted to showing the effects off, in exacerbating long takes and protracted sequences in which the narrative comes to a complete halt to stop and gawk: at the newly re-designed U.S.S. Enterprise, at the massive cloud-covered alien spacecraft V'Ger, at the interior spaces with their blinking lights and shiny readouts (and a really bad case of the late-'70s earthtones, captured with unusual flatness given how extensively visual the rest of the film is), at just plain stars, drifting by.

There's a certain anthropological appeal to all this: in 1979, here's what the state of the art looked like. And even the longest, most indulgent, least necessary sequences are saved, at least partially, by the film's awe-inspiring score by Jerry Goldsmith - in a walk, the best music composed for any iteration of Star Trek, beginning with his adrenaline-shot of bombast in an opening theme so potent and elemental it was re-purposed as the main title theme of TV's Star Trek: The Next Generation, eight years later, and continuing through a martial, atonal motif for the warlike Klingons, itself repurposed multiple times over the years, and into the bellowing, non-musical sounds used as V'Ger's theme. But it is impossible not to concede to the film's earliest critics: yes, The Motion Picture is pretty goddamned boring. And not just because it is slow, lingering over each and ever scene at least a third again too long; not just because it has too many narrative dead-ends scattered throughout far too long a running time - a totally un-functional sequence involving a wormhole is by far the most obvious offender - but because it gives its characters nothing all to do but traipse through the plot, and Star Trek has always been at its best when it lets its main trio of characters interact: brash captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner), rigidly un-emotional half-human, half-Vulcan Spock (Leonard Nimoy), irascible doctor Leonard "Bones" McCoy (DeForest Kelley). They get enough of a chance to play around within movie that you can recognise the personalities from the show, but for the most part, they're props in their own movie, and that's not even talking about how badly the film manhandles the rest of the classic cast. Spock gets a bit of a plot arc that's not well-managed by Nimoy's obvious rustiness with the character, and Kirk has to do a minute amount of soul-searching that serves mostly to mark time before the plot kicks off, but in the best tradition of "serious" movie sci-fi, the human element of The Motion Picture is kept at arm's length, and only the residual warmth of these characters as established by an old TV show keeps the whole thing from being totally and completely sterile.

Simply put, it doesn't tell a story worth the telling. There's too much arbitrary set-up: the crew has dispersed since the end of the series, but not for any reason that's used to such great effect that it had to be the case, especially since the only plausible excuse, to introduce the characters to new viewers, doesn't end up applying (the exposition is almost entirely dedicated to catching up the faithful, not bringing in newbies). The eventual conflict has some interesting ideas, even ideas that would have fit well in a 48-minute TV episode; but it takes much too long to get to the remotely interesting material about the need for intelligent beings to communicate with their gods, with a whole lot of static, dramatically uncompelling space mystery filling it out.

In 2001, Robert Wise was able to complete a director's cut for DVD, and in fairness: this version is so much better than the theatrical cut (or the borderline-unwatchable VHS "extended" cut, so pokey that calling it "boring" is laughably insufficient) that it really isn't the same movie anymore. The film was rushed through post-production, and neither the visual effects nor the editing had arrived where the filmmakers wanted. To fix things, Wise supervised the insertion of new CGI effects designed to look as much as possible like 1979 model work, numerous scenes were shaved down, and the whole thing flows infinitely better. It's still not a very exciting movie, but at least its slowness feels stately and intentional, rather than out of control and soporific. Prior to this version, The Motion Picture was my second-least-favorite of all nine (at the time) movies; it has since jumped up to be more in the middle. It still has character problems, and it is still far too concerned with staring at spaceships as gorgeous music plays and not with having those spaceships do anything (the set-up phase ends, and the "plot" begins, a solid 45-minutes into the 136-minute director's cut - a huge amount of waiting for a movie with "trek" in its damn title). But at least it has something resembling momentum, and though it still fails to marry the swashbuckling of Star Wars with the thoughtfulness of 2001 in the way it plainly wants to, it's not as grueling in that failure. Still, the film series had nowhere to go but up, and it very quickly went there.

Reviews in this series

Star Trek: The Motion Picture (Wise, 1979)

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (Meyer, 1982)

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (Nimoy, 1984)

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (Nimoy, 1986)

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (Shatner, 1989)

Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (Meyer, 1991)

Star Trek: Generations (Carson, 1994)

Star Trek: First Contact (Frakes, 1996)

Star Trek: Insurrection (Frakes, 1998)

Star Trek: Nemesis (Baird, 2002)

Star Trek (Abrams, 2009)

Star Trek Into Darkness (Abrams, 2013)

Star Trek Beyond (Lin, 2016)

Hindsight makes the movie much easier to take, certainly: both in knowing that compared to something as spectacularly worthless as Star Trek: Nemesis, The Motion Picture is pretty decent, in fact, and also in knowing that with genuinely excellent movies in the franchise's immediate future, it doesn't have to bear the weight of being "The Star Trek movie we've been waiting for all these years", but merely a Star Trek movie, one of many. Still, it's easy to understand what a singularly deflating experience it must have been for the first audiences, who'd been keeping the fires lit for the series ever since it was unceremoniously cancelled a decade earlier, only to find its bright, Western-influenced sense of space adventure replaced by a lugubrious sense of self-seriousness in which the free humor of the TV show had been banished to a few character moments included more as a sop to the fans than an integral part of the movie.

This state of affairs was by no means an accident. The reason that a half-decade of attempts to launch a Star Trek feature, or a new TV series (under the name Star Trek: Phase II) finally ended in success has nothing at all to do with the dogged perseverance of creator Gene Roddenberry, and mostly because in 1977, Star Wars made an amount of money that you wouldn't have even joked about before it opened. Overnight, every studio wanted their own massive sci-fi epic to jump on that bandwagon ASAP, and Paramount had the good fortune of already owning a sci-fi franchise with a built-in fanbase and something like brand recognition even among those who weren't fans. It even had "Star" in the title. On the other hand, the people responsible for bringing Star Trek to cinemas were eager to distinguish their property from George Lucas's rousing but trivial space opera, by emphasising the philosophical side, the serious side, the "hard" side of Star Trek. A series that had never, before 1979, ever had the slightest inclination towards hard sci-fi.

So the expectation that The Motion Picture would be something like Star Wars but with more humanism and a sense of exploration rather than action - would be the thing the show always was - was already doomed by the time that a shooting script was finally selected out of God knows how many false starts. But faulty expectations aren't reason enough to declare The Motion Picture an outright failure. In fact, there's a lot about the movie that works: starting with the selection of Robert Wise as director, easily the most talented man ever put in charge of a Star Trek feature, and at the level of pure cinematic language, The Motion Picture is still probably the "best" movie in the franchise; most of them have the unmistakable aura of TV directors hanging around, but Wise was unmistakably looking to make a real, proper feature film - a Motion Picture if you will, and not just a movie like the subsequent eleven Star Trek pictures - and divorced from anything else, he succeeded. The Motion Picture is a gorgeous movie, with the best visual effects of 1979; it had the pedigree for it, with the visual effects team led by Douglas Trumbull, of the groundbreaking 2001: A Space Odyssey and the exemplary Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Star Wars' own John Dykstra.

In fact, the outstanding visual effects work is directly responsible for one of the easiest and most accurate criticisms of the movie: some much time and energy and money was spent perfect the VFX, and in those days, effects of this kind were so excitingly novel, that a deeply unnecessary percentage of the film's running time is devoted to showing the effects off, in exacerbating long takes and protracted sequences in which the narrative comes to a complete halt to stop and gawk: at the newly re-designed U.S.S. Enterprise, at the massive cloud-covered alien spacecraft V'Ger, at the interior spaces with their blinking lights and shiny readouts (and a really bad case of the late-'70s earthtones, captured with unusual flatness given how extensively visual the rest of the film is), at just plain stars, drifting by.

There's a certain anthropological appeal to all this: in 1979, here's what the state of the art looked like. And even the longest, most indulgent, least necessary sequences are saved, at least partially, by the film's awe-inspiring score by Jerry Goldsmith - in a walk, the best music composed for any iteration of Star Trek, beginning with his adrenaline-shot of bombast in an opening theme so potent and elemental it was re-purposed as the main title theme of TV's Star Trek: The Next Generation, eight years later, and continuing through a martial, atonal motif for the warlike Klingons, itself repurposed multiple times over the years, and into the bellowing, non-musical sounds used as V'Ger's theme. But it is impossible not to concede to the film's earliest critics: yes, The Motion Picture is pretty goddamned boring. And not just because it is slow, lingering over each and ever scene at least a third again too long; not just because it has too many narrative dead-ends scattered throughout far too long a running time - a totally un-functional sequence involving a wormhole is by far the most obvious offender - but because it gives its characters nothing all to do but traipse through the plot, and Star Trek has always been at its best when it lets its main trio of characters interact: brash captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner), rigidly un-emotional half-human, half-Vulcan Spock (Leonard Nimoy), irascible doctor Leonard "Bones" McCoy (DeForest Kelley). They get enough of a chance to play around within movie that you can recognise the personalities from the show, but for the most part, they're props in their own movie, and that's not even talking about how badly the film manhandles the rest of the classic cast. Spock gets a bit of a plot arc that's not well-managed by Nimoy's obvious rustiness with the character, and Kirk has to do a minute amount of soul-searching that serves mostly to mark time before the plot kicks off, but in the best tradition of "serious" movie sci-fi, the human element of The Motion Picture is kept at arm's length, and only the residual warmth of these characters as established by an old TV show keeps the whole thing from being totally and completely sterile.

Simply put, it doesn't tell a story worth the telling. There's too much arbitrary set-up: the crew has dispersed since the end of the series, but not for any reason that's used to such great effect that it had to be the case, especially since the only plausible excuse, to introduce the characters to new viewers, doesn't end up applying (the exposition is almost entirely dedicated to catching up the faithful, not bringing in newbies). The eventual conflict has some interesting ideas, even ideas that would have fit well in a 48-minute TV episode; but it takes much too long to get to the remotely interesting material about the need for intelligent beings to communicate with their gods, with a whole lot of static, dramatically uncompelling space mystery filling it out.

In 2001, Robert Wise was able to complete a director's cut for DVD, and in fairness: this version is so much better than the theatrical cut (or the borderline-unwatchable VHS "extended" cut, so pokey that calling it "boring" is laughably insufficient) that it really isn't the same movie anymore. The film was rushed through post-production, and neither the visual effects nor the editing had arrived where the filmmakers wanted. To fix things, Wise supervised the insertion of new CGI effects designed to look as much as possible like 1979 model work, numerous scenes were shaved down, and the whole thing flows infinitely better. It's still not a very exciting movie, but at least its slowness feels stately and intentional, rather than out of control and soporific. Prior to this version, The Motion Picture was my second-least-favorite of all nine (at the time) movies; it has since jumped up to be more in the middle. It still has character problems, and it is still far too concerned with staring at spaceships as gorgeous music plays and not with having those spaceships do anything (the set-up phase ends, and the "plot" begins, a solid 45-minutes into the 136-minute director's cut - a huge amount of waiting for a movie with "trek" in its damn title). But at least it has something resembling momentum, and though it still fails to marry the swashbuckling of Star Wars with the thoughtfulness of 2001 in the way it plainly wants to, it's not as grueling in that failure. Still, the film series had nowhere to go but up, and it very quickly went there.

Reviews in this series

Star Trek: The Motion Picture (Wise, 1979)

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (Meyer, 1982)

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock (Nimoy, 1984)

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (Nimoy, 1986)

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (Shatner, 1989)

Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country (Meyer, 1991)

Star Trek: Generations (Carson, 1994)

Star Trek: First Contact (Frakes, 1996)

Star Trek: Insurrection (Frakes, 1998)

Star Trek: Nemesis (Baird, 2002)

Star Trek (Abrams, 2009)

Star Trek Into Darkness (Abrams, 2013)

Star Trek Beyond (Lin, 2016)

12 comments:

Just a few rules so that everybody can have fun: ad hominem attacks on the blogger are fair; ad hominem attacks on other commenters will be deleted. And I will absolutely not stand for anything that is, in my judgment, demeaning, insulting or hateful to any gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or religion. And though I won't insist on keeping politics out, let's think long and hard before we say anything particularly inflammatory.

Also, sorry about the whole "must be a registered user" thing, but I do deeply hate to get spam, and I refuse to take on the totalitarian mantle of moderating comments, and I am much too lazy to try to migrate over to a better comments system than the one that comes pre-loaded with Blogger.

The clearest indicator that the director/editor et. al. lost complete control of the movie's running time is this dialogue exchange between Kirk and Decker on the bridge. Kirk wants to travel into the V'ger cloud but Decker advises caution.

ReplyDeleteDecker: Moving into that cloud at this time, is an unwarranted gamble.

Kirk: How do you define 'unwarranted'?

[A whole shitload of intricate, expensive visual effects ensue as the Enterprise moves into the cloud, flies over V'ger, is invaded by a probe which zaps Ilya into nothingness]

Decker: THIS is how I define 'unwarranted'!

That's 13 minutes, 37 seconds of elapsed screen time between Kirk's question and Decker's answer.

I have always enjoyed TMP because I felt it was the movie which most represented the Star Trek ethos. I love Khan, don't get me wrong. But Star Trek was never supposed to be martial. I really enjoy the Nick Meyer movies because they have great story and character and blatant literary steals which are fun. But there is just something so... Star Trek about the first movie.

ReplyDeleteThere is an ethereal beauty about TMP and when you combine that with the philosophical story of what it means both to be human and to find a creator, I think the movie is an under-appreciated triumph.

Yes, it is too long. I read they were so behind that at the premier the print was still wet. They could have edited the movie down to about 110 minutes. Yes, it is largely people staring at screens.

This is one of those movies where you shake your head and say, "So close."

If they had more time, I think Wise could have really made something out of it.

The eventual conflict has some interesting ideas, even ideas that would have fit well in a 48-minute TV episode

ReplyDeleteThat's probably because they did: it's a reasonably decent clone of The Changeling, where Kirk has to out-think the -V-o-y-a-g-e-r- Nomad space probe. Which is hardly a fair reason to knock the movie, but it doesn't help the whole "this should be 40% as long" problem.

I liked this the first time I saw it. I REALLY liked it the second time I saw it. On acid.

ReplyDeleteThis is maybe the only film in the entire series that preserved the core values and philosophies of the show and Rodenberry's original vision. Mystery, exploration, unknown, it's all pretty heady stuff, or at least high-concept. And as a fan of long, pornographic shots of old-timey effects, this movie hits a few points for me.

I'm interested to get into the TNG movies with you, I think they're all creatively bankrupt garbage. Can't wait to see what you think!

I hated this movie as a kid, growing up watching TOS episodes with my dad. As an adult, watching the superior Director's Cut, I like it a lot more, but yeah...it'll never be one of my favorites.

ReplyDeleteI am super excited we're getting Star Trek reviews!

I remember seeing this back in 1979, as a teen proto-Trekkie. That first 45 minutes of gathering the crew together was just wonderful; here were the people that we had been waiting to see again for over a decade, together once more. Each character was cheered, although that first glorious view of the Enterprise earned the biggest cheers.

ReplyDeleteAnd yes, then there's the rest of the film. But I mostly remember that first part, saying hello to everyone. I suspect it doesn't translate well now, given all of the movies and the ability to watch them (as well as the TV shows) whenever because of video. But at the time, as the culmination of years of fan clamoring to have such a movie made, it was just fantastic.

I only saw this once, many years ago, and I fear it was the "borderline unwatchable" extended version, which...lived up to that characterization. This review makes me want to seek out the director's cut.

ReplyDeleteLike everyone else, I'm excited about this series. I was a huge trekkie from, oh, maybe ages thirteen to seventeen. These days, I'm afraid my interest in the franchise is very limited, but it'll be very interesting to see your takes.

I love that we've had pretty much every possible take on the movie in this comment thread.

ReplyDeleteRick- That's a truly amazing statistic.

Lisa- Glad to have somebody chime in who saw it in theaters! I first saw the movies all out of order, so it's interesting to have insight from somebody who A) had been waiting for new Trek and B) didn't have any reason to believe that there'd be more Trek yet to come.

Like a lot of movies, the production of ST:TMP is a lot more interesting and dramatic than the movie itself.

ReplyDeleteThe company originally hired to do the visual effects was fired in post production because by all appearances it looked like they wouldn't be able to finish in time for the premiere.

So with only 8 months to go, Douglas Trumbull was hired as a replacement. What made this particularly dire was that principal photography had already wrapped, so Trumbull was handed a whole bunch of footage and told to complete the shots, without having any idea what the original plan for it had been.

So FX like the trippy wormhole scene, or the V'ger-probe-on-the-bridge scene had to be done completely on the fly.

The Enterprise model had already been built, but it's glossy white, shiny paint job made traditional bluescreen matting techniques impossible, so an alternate approach needed to be invented from scratch.

John Dykstra and his company Apogee was brought on to help with the workload, taking the Klingon attack sequence and V'ger flyover sequences (and maybe the Epsilon 9 scenes as well. it's been a long time since I've read up on it).

The whole thing was an immense clusterfuck. Like you said, this is the best visual effects of 1979, made only more amazing if you know the behind-the-scenes drama. That they made the release date at all is incredible.

The Enterprise model was huge, about eight feet long, much larger than typical spacecraft miniatures would be. Trumbull's crew hated dealing with it, for the paint job but also the unwieldly size of it.

ReplyDeleteWhen ILM was hired to take over the FX for the franchise, they were forced by budget constraints to reuse the same filming miniature. It was a cause of huge celebration when they blew it up at the end of "Star Trek III: The Search for Spock".

All subsequent versions of the Enterprise were built to a more manageable scale.

/FX nerd

I'm enjoyed The Motion Picture quite a bit but I've been a Star Trek fan since watching TNG throughout my childhood so I'm fairly forgiving in my Star Trek film standards. However, pretty much all the criticisms of it being to stately are sound, which I don't feel negates the coolness of the psychedelic space freak-out sequences. I love space trip outs from 2001 to Tree of Life and hopefully soon to be Gravity.

ReplyDeleteI saw this movie again recently for the first time since adolescence, and having more experience, and knowing it was directed by the great Robert Wise, who directed The day the earth stood still, I think I have a better idea of what they were trying to do. The glacial pace, the deadly seriousness, the lingering effects shots, the momochromatic color scheme, the philosophical musings about the meaning of life and man merging with machine -- they were trying to make a movie like 2001 A Space Odyssey. Not Star Wars at all. I don't think they succeeded, but at least now I understand better where it's coming from.

ReplyDelete